Lured by the excitement of gold discoveries in America, Australia, and in the newly settled colony of New Zealand, my 4x great-uncle, John Ewart, and his friend Joseph Porthouse boarded the John Masterman and set sail for New Zealand in mid-October 1857. 1 As they embarked on this daring journey, little did John know it would mark the beginning of a new chapter in his life, far from the village of Crosby-on-Eden where John spent his childhood.

John, born between 1828 and 1831 to John Ewart and Ann Little in Crosby-on-Eden, Cumberland, England, was baptized on 20 November 1831. 2 He was the eldest of eight children. His father, a shoemaker, farmer, and butcher, along with his wife, raised their family in this village on the outskirts of Carlisle.

Crosby-on-Eden is the combined name for two small villages, High Crosby and Low Crosby near the river Eden northeast of the City of Carlisle and is less than 15 miles from the Scottish border. Carlisle underwent significant transformation during the early 19th century with the establishment of factories, textile mills, and engineering endeavors, leading to a notable increase in population. 4

In 1851, as overpopulation, housing shortages, and low wages plagued Carlisle and its suburbs, John Ewart found himself working as a farm servant in the nearby town of Linstock. 5 The economic challenges of the time likely influenced his decision to seek new opportunities abroad. Ultimately, he embarked on a daring journey to New Zealand in search of a better life amid the fervor of gold rushes sweeping across the far reaches of the world.

Journey to New Zealand

During the early 19th century, New Zealand was regarded as the most distant and secluded location on the planet. Situated in the South Pacific Ocean, it was initially inhabited by the Māori people, who are of Polynesian descent. New Zealand was colonized by the British in 1840 after some dubious land purchases by the New Zealand Company from the Maiori. 6 To most Europeans, New Zealand seemed uninviting – a strange, unfamiliar and isolated land only accessible after 100 perilous days at sea. 7 Immigration to New Zealand was driven by the potential for higher wages and a better life abroad. 8

John endured a harrowing ordeal, lasting four months at sea. 9 The voyage began on a gloomy day as the vessel departed England amidst sleet, a biting northeast wind, and thick fog. 10 Throughout the voyage he and his fellow passengers faced turbulent seas, relentless cold, and persistent dampness. 11 The passengers faced the daunting task of preparing meals using only their own tools and utensils, while sharing a single fire for cooking. 12 The presence of rats and cockroaches only added to their discomfort. 13

To make matters worse, John traveled in steerage, 14 confined to cramped, dimly lit bunks below deck along with approximately 100 others for the duration of the voyage. 15 Physical discomfort, limited resources, and crowded conditions tested everyone’s endurance and resilience onboard.

Search for Gold

After arriving in Nelson, New Zealand’s oldest city, on 8 February 1857, John spent some years at the Collingwood diggings, joining the surge of fortune hunters. 16 The discovery of payable gold deposits in the Aorere Valley in 1856 triggered a population boom in the region, transforming small settlements into bustling mining towns. At the time the Collingwood settlement consisted of just two tents, but a year later, it grew to seven hotels and had a population of 700 Europeans and 200 Maori. 17 The gold rush in the Aorere Valley lasted three years.

Amid New Zealand’s development, John embarked on a quest for prosperity and fresh beginnings likely influenced by the impact of British colonization. Despite the uncertainty surrounding John’s success in striking gold, his decision to remain in New Zealand suggests that he found fulfillment beyond material wealth.

Settling In

John settled nearby in an area known as the Beaver, aptly named for its frequent flooding. Located at the edge of the Wairau Valley, it was not much of a town then, just a few scattered houses situated amid a swampy district. 18 In 1859, the Beaver became part of the newly formed province of Marlborough when it split from Nelson and the town was renamed Blenheim. 19

Shortly after securing a job as a constable, John ran into trouble when he accidentally set fire to a storekeeper’s bush, landing him a two-month stay in Nelson gaol [jail]. 20 Lucky for him, Nelson was no longer taking prisoners from the newly formed province of Marlborough. After two or three years in the police force, he resigned and started in business as a publican at the old Marlborough Hotel. 21

Family Life and Business Ventures

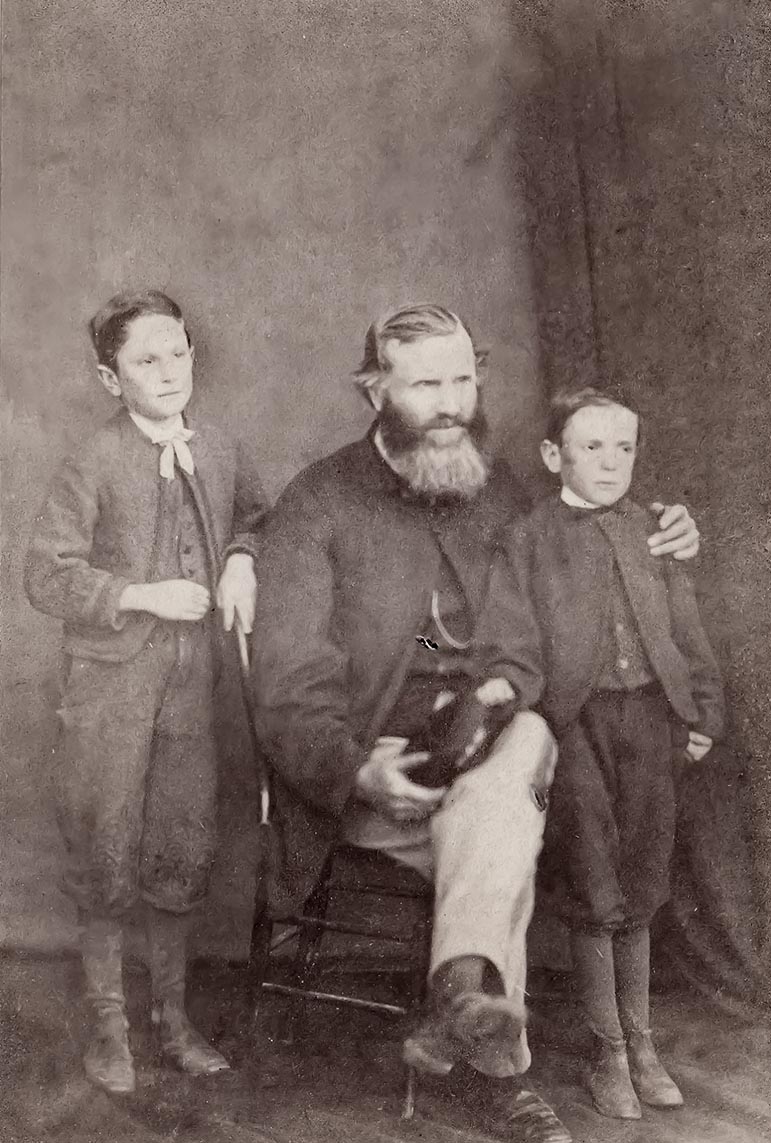

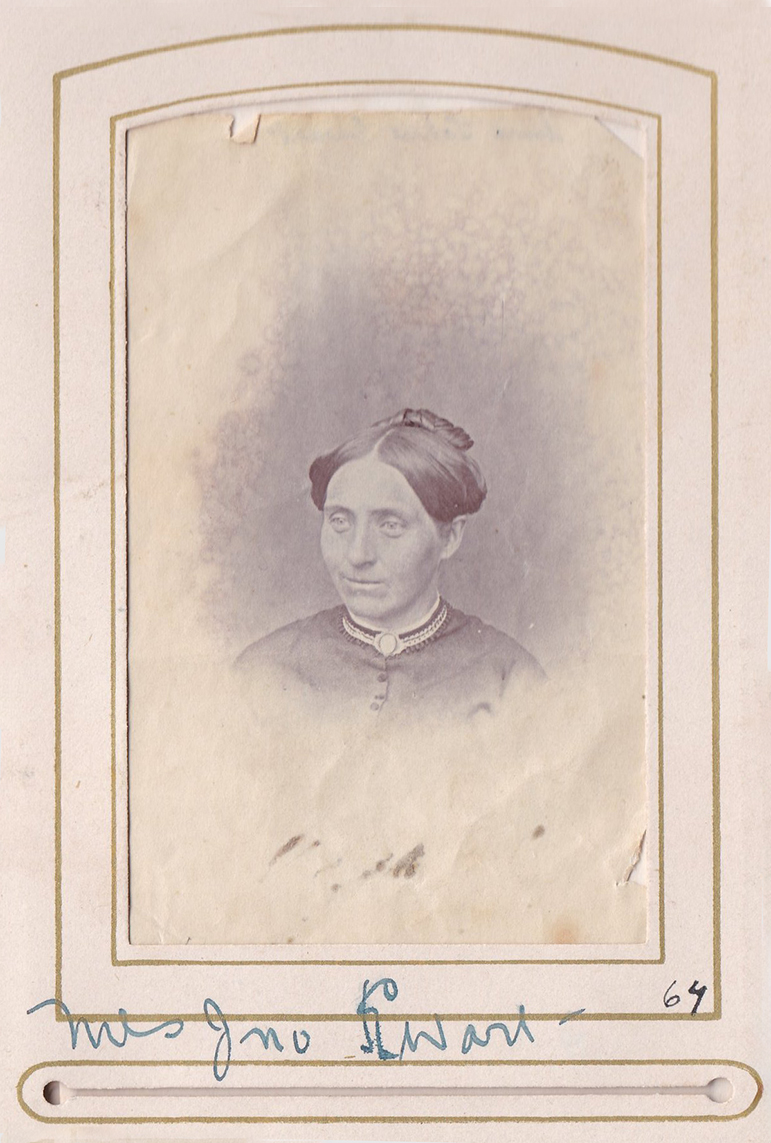

John married Hannah Harrison on October 17, 1860, at the residence of their close friend Joseph Porthouse in Nelson.22 They had six children together, Joseph, Annie, Edward and Margaret Jane. 23 A set of twins died at birth. 24

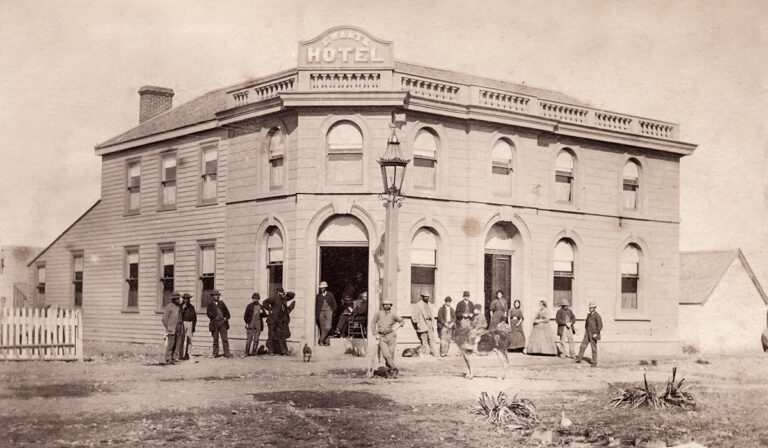

Known as a premier innkeeper, John was kind and generous, often lending people money, sometimes large amounts when requested. 25 Hotels flourished in this area during the gold rushes and John’s establishment stood out among the accommodation options of the time. 26 He purchased a hotel from James Reid, a friend from England. 27 In 1868 John erected Ewart’s Hotel on High Street in Blenheim. 28

In late January 1869, John received a telegram informing him of the melancholy death of his good friend Joseph Porthouse who took his own life by cutting his throat. 29 John immediately set out for Nelson to attend the funeral only to find another telegram awaiting him bearing the shocking news that James Reid, another friend had also died in the same manner. 30 Even more haunting is that John recognized the razor used by Porthouse as one given to him as a gift by James Reid. The three friends had known each other in England and had come to the colony together. 31

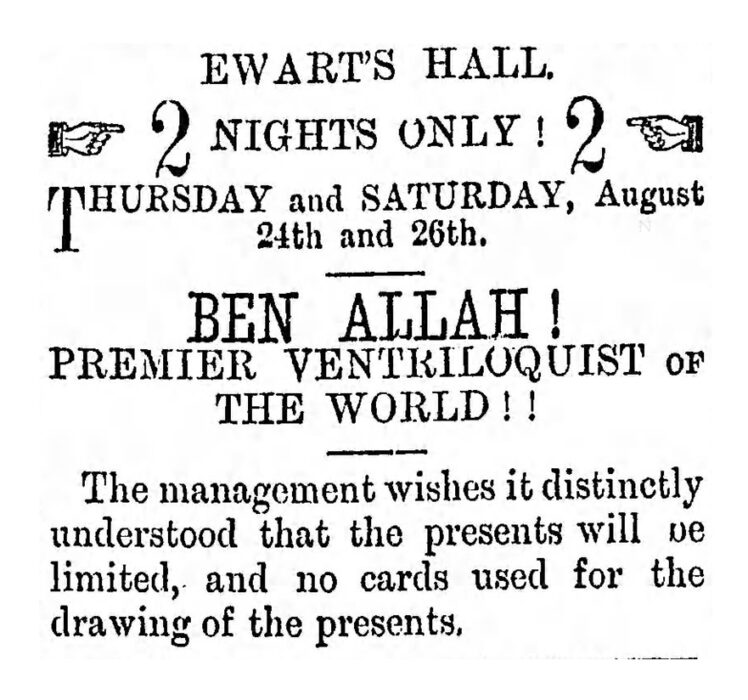

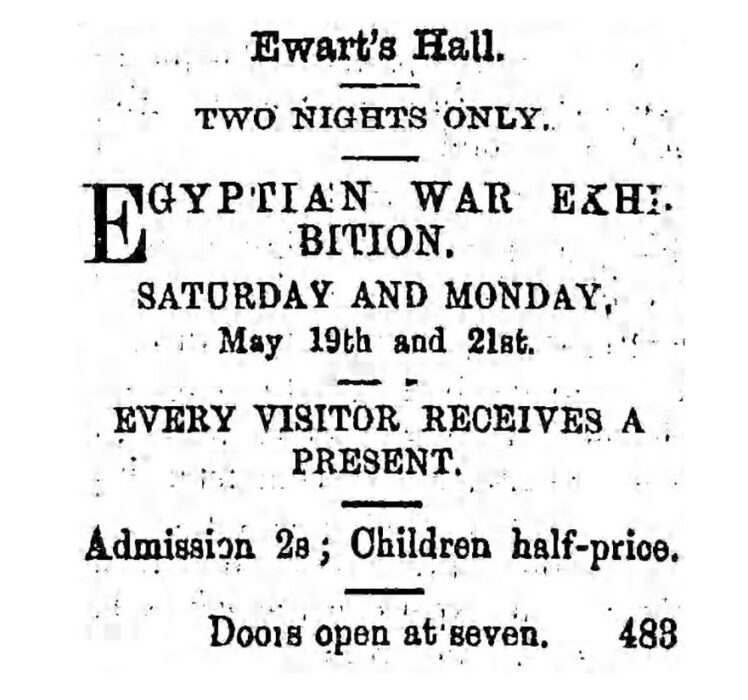

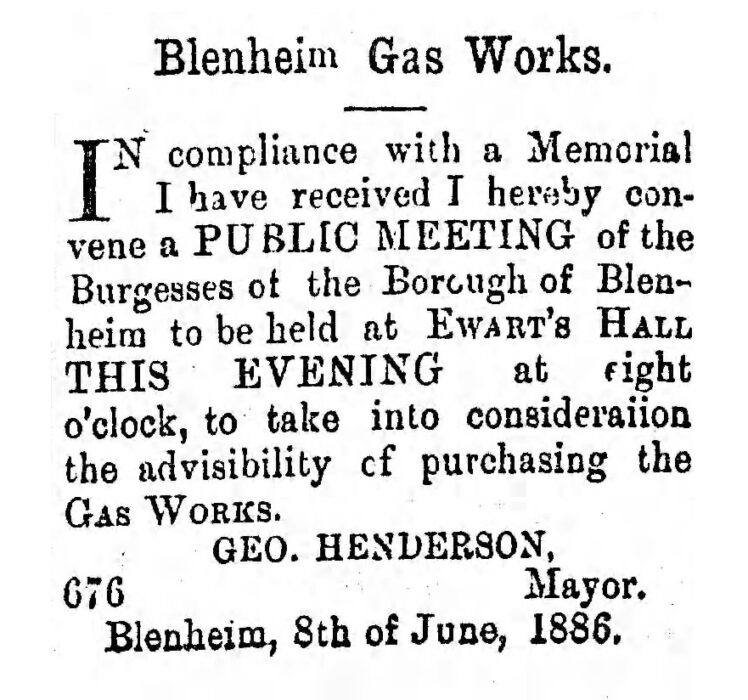

In 1873, John opened Ewarts Hall, a theater that quickly became a central hub for the community. 32 This multipurpose venue hosted various town meetings, events, entertainment shows, educational lectures, and fairs, serving as a vital space for both social gatherings and cultural activities.

His wife Hannah, died at the age of 41, on 21 January 1874. 33 A significant gathering, led by several Oddfellows and Forresters, trailed the funeral procession, spanning over a quarter-mile. All were eager to offer their sympathies to the grieving family. 34 She is buried at Omaka Cemetery in Blenheim. 35

One year later on 27 January 1875, John married Margaret “Jane” Kennedy at Ewart’s Hotel by Father Sauzeau. 36 He and Jane had 7 children together, Mary Ellen, William James, George Gladstone, Marth Hyacinth, John, Eileen Fanny and Edina Rufina Carlisle. 37

The hotel was destroyed by a fire on 2 November of 1876 also taking out at least a dozen businesses on High Street, leaving Ewart’s Hall unharmed. 38 In 1877, John started construction on a new hotel that was known as the Marlborough Club Hotel. 39 It stood on two levels, with ten bedrooms, a banquet hall, and a room reserved for the Masonic Lodge. The first level housed a parlor, bar, dining room, kitchen, two bedrooms, a billiard room, and a club room reserved exclusively for the Marlborough Club. 40

Retirement

Having amassed enough property and resources to live a comfortable life, John retired to his home on Maxwell Road. 41 Although he didn’t actively participate in public affairs, he maintained a keen interest in issues impacting the growth and development of Blenheim. 42

Final Days

A short time before his death, John took a trip to Sydney to seek medical advice. 43 Doctors told him that if he wished to see New Zealand again he better return at once.44 He was laid up in Wellington before being able to return to Blenheim. 45 John died of Bright’s disease on 27 December 1891 at his home.46 He is buried in Omaka cemetery.47

John Ewart’s journey from the villages of Cumberland to the untamed wilderness of New Zealand’s gold fields offered him a golden opportunity. Perhaps it was the majestic mountains that drew him, the allure of fortune, or his thirst for adventure that led him to stay. Despite the challenges he faced, John found a sense of belonging, choosing to remain in his newfound home.