Daylight savings time got me thinking about my ancestors who were clock and watchmakers. Edward Goldsworthy and James Knowles set up shops mainly in the Chelsea section of London at a time when British watchmaking was at its prime. British watchmaking hit its peak by 1800 exporting almost half the worlds watches with exports around 200,000 watches per year. 1

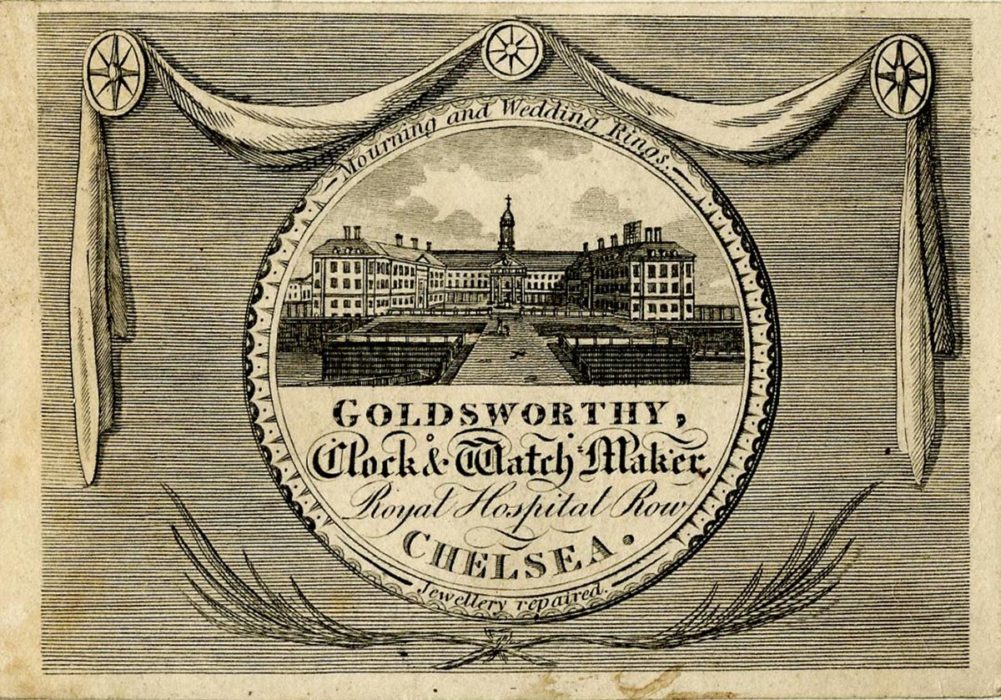

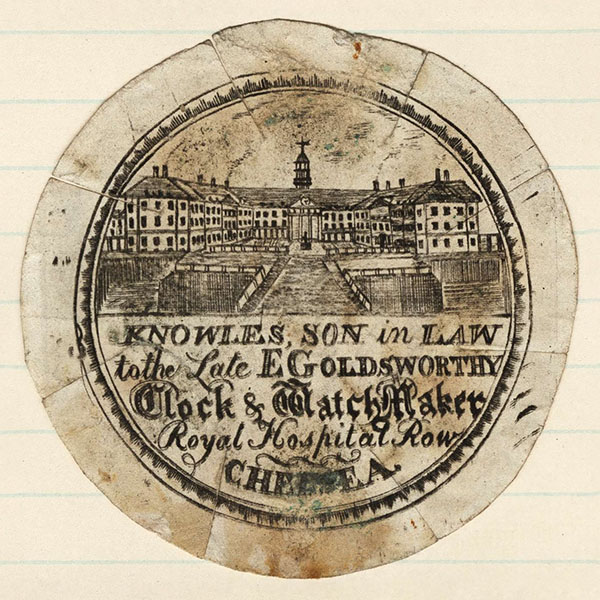

It was exciting to learn that James and Edwards’ watchpapers are held at the British Museum in London. 2 Popular during the 1700-1800s, watchpapers are round, decorative papers that are inserted inside the case of a pocket watch. They also served as advertisements with the address printed on the front and on the back were the date of manufacture or a log of repairs. 3 Edwards’ trade-card is also held by the museum as seen in the image at the top. 4

Edward Goldsworthy was my great-great-great-great-great grandfather. He was the son of William and Jane Goldsworthy and was baptized at Saint Mary Major, Exeter, Devon, England on 20 December 1751. 5 In 1765 Edward apprenticed under master watchmaker George Flashman. 6 For whatever reason, Edward did not finish his apprenticeship with Flashman and in 1766 he apprenticed with master clock and watchmaker, William Hornsesey. 7 By 1788, Edward was a master clock and watchmaker in Exeter and took on an apprentice of his own. 8 By 1794 he had moved to Norton Folgate of the Tower Division adjacent to the City of London. 9

James Knowles, my most distant known Knowles ancestor, was probably born about 1779 in Nayland, Suffolk, England to Joseph and Jane Knowles. 10 He married Ann Goldsworthy, the daughter of Edward Goldsworthy 22 June 1801 at Christ Church, Spitalfields in the Tower Hamlets division. 11 I descend through James and Ann’s son Edward Knowles.

What brought these two men to London is not known but it seems likely that they worked together. Although no apprenticeship records are found at this time, it is likely that James apprenticed under Edward sometime before his marriage to Ann. 12 When Edward died in 1824, James took over his father-in-law’s business on Royal Hospital Row in Chelsea. 13

Luckily there are still some examples of their work out there.

Edward Goldsworthy

18th century longcase clock by Edward Goldsworthy | © Garth Denham and Associates Limited.

James Knowles

English bracket clock by James Knowles of London, 1840. | © www.kdclocks.co.uk

While watchmaking was at its height by 1800, a national time standard wasn’t established until 1880 when Greenwich Mean Time became law. Almost all public clocks in Britain were set to Greenwich Mean Time by the mid-1850s. Before then local towns kept their own time based on the sun. Neither the start nor end of the day or the length of an hour were standard. Similar to Daylight Savings Time, British Summertime was established in 1916 which is one hour ahead of Greenwich Mean Time. Thus mornings have one hour less daylight, and evenings have one hour more. 14 It makes me wonder what Edward and James would have thought about a national time standard or even a version of daylight savings time. Perhaps they would have said “it’s about time”.