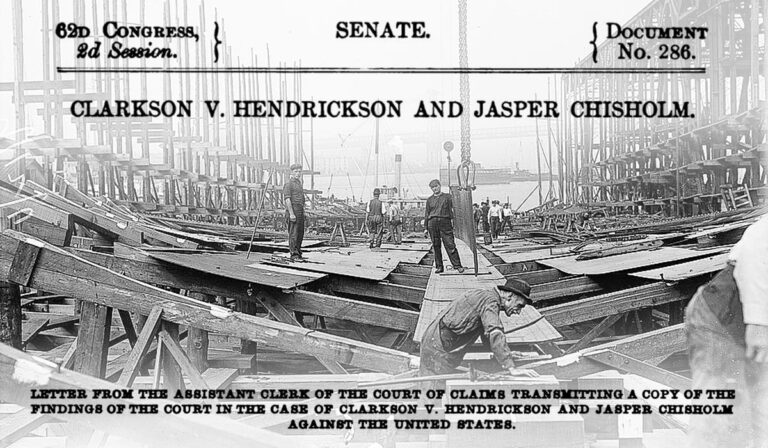

My great-great-grandfather Clarkson V. Hendrickson, Sr., and Jasper Chisholm, a coworker, filed a claim against the United States in 1912 for payment of overtime work at the Brooklyn Navy Yard between 21 March 1878 and 22 September 1882. 1 While I couldn’t find independent evidence that Clarkson worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during those years, census records show he was an office clerk in 1880, but it doesn’t show his place of employment. 2 Official U.S. Registers of civilian and military employees show that he worked there as a blacksmith apprentice in 1883 and 1885. 3

And before anyone asks where the money went—he lost. All $35.96 of it.

Legal Background

The Tucker Act of 1887 allowed people and organizations to sue the U.S. government for financial claims under three conditions: contractual claims, noncontractual claims for refunds, or noncontractual claims for those entitled to payment by the government. 4

So why did Clarkson and Jasper wait until 1912 to sue for back pay? Who knows, but that is where they went wrong. Sadly, Jasper passed away before the court heard their case. Their inspiration may have come from a local newspaper article published in 1907. It highlighted the efforts of NYC lawyer George Hiram Mann, a crusader for navy yard workers seeking overtime pay. 5 Mr. Mann conducted a successful test case and believed that many claims would receive full payment. 6 It was a battle that Mr. Mann would wage for decades to come.

In 1908, the Senate referred a bill to the Court of Claims, authorizing the Secretary of the Treasury to compensate workers for overtime beyond eight-hour days in U.S. navy yards, as directed by a March 21, 1878, Navy Circular. 7 Although it was referred to in his claim, I have found no evidence that officials passed the bill into law.

The court heard the case on 8 January 1912. 8 After presenting the evidence and considering the briefs and arguments the court presented its findings.

What the Court had to Say:

The claimants were employed by the government of the United States between 21 March 1878 and 21 September 1883 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York. 9 During this time, the order of Circular No. 8 was in force by the U.S. Navy Department. 10

Navy Circular No. 8:

“The following is hereby substituted to take effect from this date, for the circular of October 25, 1877, in relation to the working hours at the several navy yards and shore stations: The working hours will be, from March 21 to September 21, from 7 a. m. to 6 p. m., from September 22 to March 20, from 7.40 a. m. to 4.30 p. m., with the usual intermission of one hour for dinner. The department will contract for the labor of mechanics, foremen, leading men, and laborers on the basis of eight hours a day. All workmen electing to labor ten hours a day will receive a proportionate increase of their wages. The commandant will notify the men employed or to be employed of these conditions and they are at liberty to continue or accept employment under them or not.” – R.W. Thompson, Secretary of the Navy 11

The court acknowledged that Clarkson worked in excess of eight hours a day as follows: 12

- 160 2/3 hours at 98 cents per day

- 103 hours at $1.02 per day

- 21 hours at $1.20 per day

If eight hours constituted a day’s work, from 21 March 1878 to 22 September 1882, under Circular no. 8, then Clarkson V. Hendrickson was underpaid $35.96. 13 That amounts to about $1,170.02 in today’s money. 14 However, the court also noted that the claimants never submitted their claims to any government department before presenting them to Congress and failed to justify the delay in doing so. 15

Ultimately, the court concluded that the claims against the United States were not legal. 16 They were only valid in that the U.S. benefited from the claimants’ services beyond the standard eight-hour workday.17

In the end, Clarkson’s case was not lost on its merits but on timing. His failure to report the issue when it occurred proved fatal to his claim. While not a client of Mr. Mann, the NYC lawyer’s 25-year battle eventually paid off. In 1935, after decades of litigation, 1,377 Navy Yard workers got the U.S. Court of Claims to acknowledge that their claims, amounting to $322,000, were valid. 18 I don’t know if Clarkson ever followed up on his claim, but hopefully, he didn’t lose his shirt in attorney fees.

It seems that this might have taken a year to research and catalogue.

You always seem to do an excellent job with your articles.

Thanks so much.